Once while studying in Pittsburgh I found myself at a happy hour with a group of philosophers, mostly philosophers of science. The discussion, as expected, was heady, but lubricated by cheap pitchers and the need to speak over the Top 40 pumping from the jukebox, there was a special gallop to the exchanges on the normally plodding topic of epistemology. At issue was the nature and rules of conceptual analysis. I leaned in:

“But what about all the thinking that is not conceptual?”

The table blinked. I had pulled up the reins—I was not a philosopher. Eventually—awkwardly—the conversation returned to where I had interrupted it, with little more than an anonymously whispered “I’m not sure what that means” to help me save face. Someone suggested the difference between Begriff and Idee, others pounced, and I leaned back.

What would I say today, if I were back among those philosophers? I might speak on imagination, wonderment, doubting—but I’m already headed off at the pass. These too can be described by the concept, they will say. Perhaps instead it is better to bring it right to the issue, the difference between concepts and topoi.

But this is not easy: rhetoric has rarely been forthcoming with many definitions of the topos, instead relying upon metaphors and example. When we say something is a “topic” we mean little more than a tag, a potential search aid, or the loosest categorization of a discourse. The topos is, on the one hand, the organizing principle of rhetorical invention—the discovery of arguments—but also can quickly fall out of the account. Averroes’ commentary on Aristotle’s Topics does not even mention what a topos is, despite the work’s title. If one is concerned with judging the quality of an argument, the topos is of little use: it exists to produce something, not evaluate it.

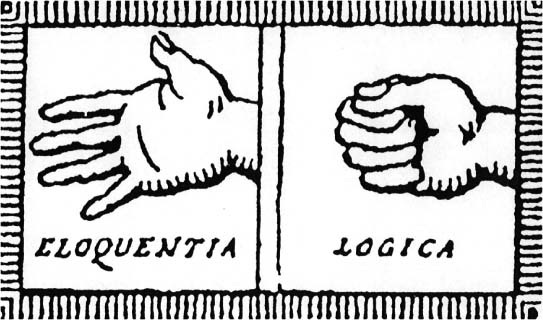

Rather than trying to define topos, we might begin by thinking about its relationship to the concept—or, in the Hochdeutsch philosophical idiom, Begriff. In Johann Christoph Adelung’s philological dictionary of German, in the second entry for Begriff, we find a more literal usage: “the space which embraces itself.”1 The example he gives is of a house: when we refer to it, we include it in what it contains. Topos, of course, literally means “place”—and Cicero translated it into Latin accordingly as locus. The topic, says Cicero, is also a kind of place or residence [quasi sedes], but it is a productive space—he says specifically a space that produces arguments. It is like a nest: a place for giving birth and raising the hatchlings. Both concept and topos refer to space that is empty, but they differ in how they understand the boundary of that space. We might recall Zeno’s famous physical demonstration of the difference between rhetoric and logic: open palm, closed fist.

But this is not simply because rhetoric is “looser” in its thinking. Concept and topos have a dialectical relation. While a concept is the rule that delimits its content, a topos generates its rule from its content. Sure, there may be a house there, but what goes on in the house will change our understanding of it: a theater, a brothel, a home? The topos seems to begin backwards: it organizes and collects its matter first, and then tries to discover what to do with it. This is one of the reasons the meaning of topos seems to change so frequently in the historical record: the rules for what can be considered the content of a topos become gradually effaced. If with Aristotle it is a set of underdetermined rules about probable inference, it can become, with Erasmus, a simple heading under which can be assigned any passage from a historical text that “speaks” it. Today, we can think about topics as having any kind of content, not only verbal, but visual, affective, or a mixed-media assemblage. Any collection becomes a topos when we approach it with a question: What is the rule that organizes this? What else could be put here?

It is, perhaps paradoxically, the rule-giving power of a topos that makes it productive—as it was understood in the ars inveniendi of Cicero—but also what makes it a common element of thought. We encounter it (namelessly) in the practice of what Charles Sanders Pierce called “abduction,” rounding out the traditional pairing of deduction and induction with his recognition of hypothetical inference. Pierce, philosopher and scientist that he was, was principally concerned with composing a logic that could adequately describe scientific activity. What philosophers of science today distinguish as the domains of justification and of discovery are, in a sense, a rediscovery of the classical distinction between syllogism and topos. While the logic of justification can be transposed into deductive syllogisms, Pierce recognized that this eliminated the hypothetical inferences that were essential to scientific discovery. While his writing on abduction is equally rewarding and abstruse, in one of his earliest writings on the topic, we are given examples that are both clear and startling. At the conclusion of his essay, he describes the difference between induction and abduction (which he then was still referring to as “hypothesis”) in light of how they appear in our bodies:

Induction infers a rule. Now, the belief of a rule is a habit. That a habit is a rule active in us, is evident. That every belief is of the nature of a habit, in so far as it is of a general character, has been shown in the earlier papers of this series. Induction, therefore, is the logical formula which expresses the physiological process of formation of a habit. Hypothesis substitutes, for a complicated tangle of predicates attached to one subject, a single conception. Now, there is a peculiar sensation belonging to the act of thinking that each of these predicates inheres in the subject. In hypothetic inference this complicated feeling so produced is replaced by a single feeling of greater intensity, that belonging to the act of thinking the hypothetic conclusion. Now, when our nervous system is excited in a complicated way, there being a relation between the elements of the excitation, the result is a single harmonious disturbance which I call an emotion. Thus, the various sounds made by the instruments of an orchestra strike upon the ear, and the result is a peculiar musical emotion, quite distinct from the sounds themselves. This emotion is essentially the same thing as an hypothetic inference, and every hypothetic inference involves the formation of such an emotion. We may say, therefore, that hypothesis produces the sensuous element of thought, and induction the habitual element. (481-2, emphasis mine)

Thought not only can discover the unity in something it experiences but also create the diversity that it gives unity to. That is the thinking of topos rather than concept. The method of topoi is the ability to produce such emotions in thought for ourselves. Emotions need not be reactions to things we passively come upon in the world. In making a topos, we are giving ourselves our own occasion for feeling and thinking. In giving a name to the feeling we have in examining a topos, however peculiar it may be, we name an inference. In this way, we might say, there is an emotion that gives birth to every conception.

Derjenige Raum welcher etwas in sich begreifet.